Breakthrough Dravet Syndrome gene therapy in mice brings new hope to families

Scientists successfully replace defective gene to alleviate symptoms without side effects.

By Liz Dueweke

In a groundbreaking advancement for families grappling with the challenges of Dravet syndrome, a rare and life-altering form of epilepsy, scientists have developed a new gene replacement therapy in mice that could lead to more effective treatments in humans. The new therapy, a collaboration between researchers at the Allen Institute and Seattle Children’s Research Institute, alleviated symptoms and led to long-term recovery without toxicity, side effects, and death.

(This movie shows SCN1A genes illuminated in neurons of a mouse with Dravet syndrome.)

“People who take drugs for epilepsy often complain that the drugs are very impactful, they can slow down the seizures but it changes a lot about their brain,” said Boaz Levi, Ph.D., associate investigator at the Allen Institute, who co-led the study with Franck Kalume,Ph.D., an associate professor at the University of Washington and principal investigator at Seattle Children’s Research Institute.

Dravet syndrome affects around 1 in 15,700 children, and most cases are caused by mutations in the SCN1A gene. This gene plays a crucial role in the brain’s ability to regulate activity through fast-spiking interneurons. With severe seizures and developmental delays, this disease has long left families and researchers desperate for more effective treatments.

These two Electroencephalogram (EEG) recordings, at 25% speed, show neural activity in mouse brains. The top recording is from a Dravet Syndrome (DS) model mouse that was treated with the SCN1A AAVs while the bottom recording is from a DS model mouse that was not treated. The untreated mouse experiences a seizure during this recording (large amplitude spikes halfway through the recording), while no seizures are observed in the treated mouse during the recorded interval.

This new therapy involves an innovative two-step strategy:

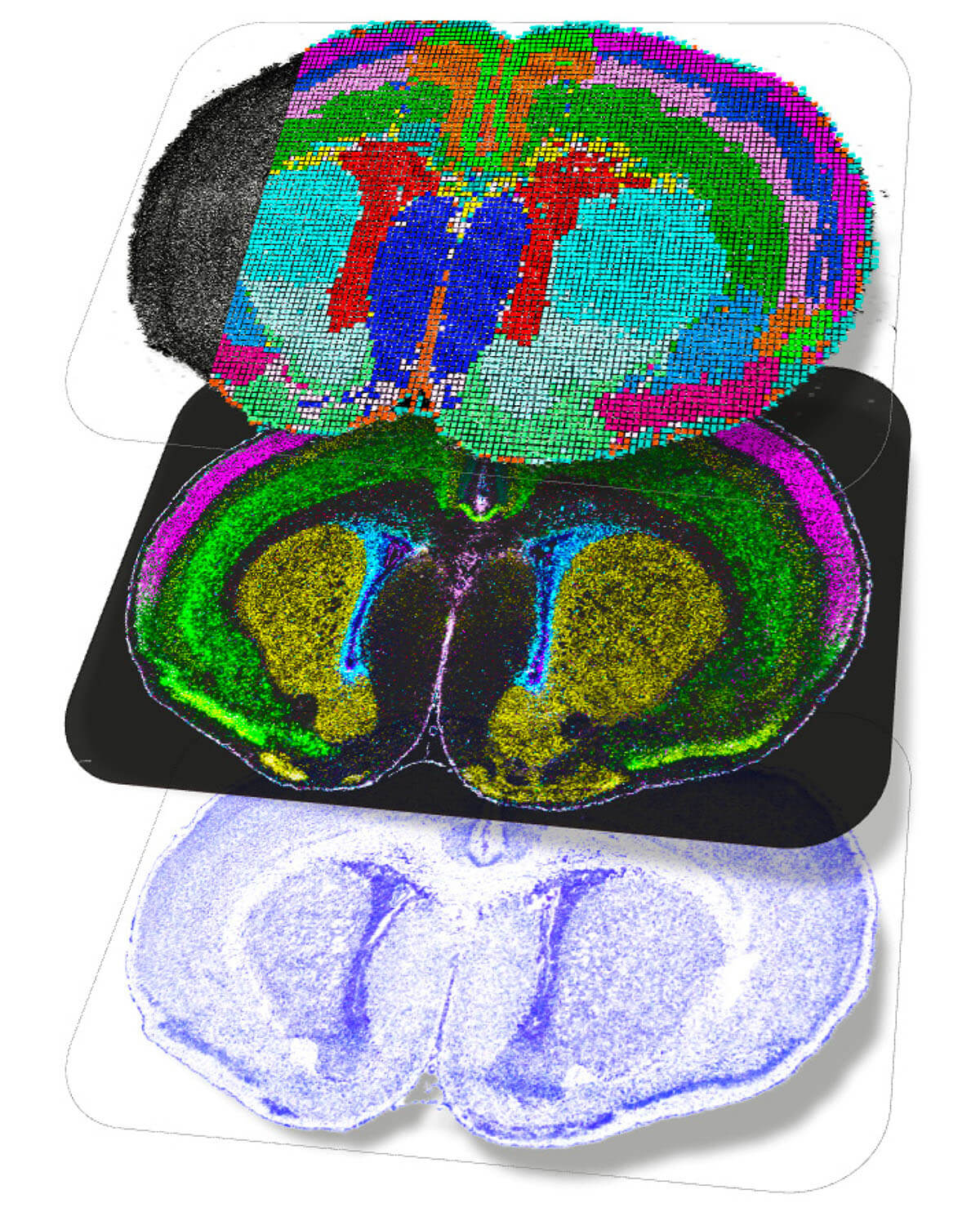

1. Precision gene delivery: Using specialized enhancers (short stretches of DNA that act like switches to control when and where a specific gene is turned on) scientists were able to target specific cells that are defective in patients with Dravet syndrome.

2. Solving the puzzle of gene size limits: Gene therapy is done through AAV vectors. These are harmless viruses that can carry genes into cells. But the SCN1A gene is too large to fit into conventional AAV vectors, so scientists overcame this hurdle by using a protein fusion mechanism which splits the gene into two parts so that it can be carried into the cell and reassembled. Each half is delivered to the same cell by a separate virus where the fuse together to make the final gene. This is like delivering a large piece of furniture into your home in two parts because it can’t fit through the front door and then reassembling it once the pieces are inside.

Treated mice in this study showed remarkable improvement: Seizures were alleviated, recovery was long-lasting, and no adverse effects were observed.

(This image shows neurons illuminated in yellow in the brain of a mouse that received neuron-specific SCN1A AAVs which work to produce safe correction of Dravet Syndrome symptoms.)

What’s next? A promising path forward

These results not only support the potential of AAV-mediated SCN1A gene replacement, but also spotlight the critical role of cell-specific therapies in combating genetic disorders like Dravet syndrome. “These are people who are going to have a severely impacted standard of living,” said Levi. “We are hopeful this sort of a therapy could have a huge impact for families, and that’s what’s exciting to me.”